MPs from all opposition parties have begun a boycott of Georgia’s parliament over the government’s U-turn on introducing proportional elections for the 2020 elections.

On Tuesday parliament reconvened for the Spring session with only MPs from the ruling Georgian Dream Party and independents attending.

It came after the Alliance of Patriots and Social Democrats group and their 7 MPs joined the European Georgia and United National Movement (UNM) parties in their boycott over the ‘broken promise’ of electoral reforms.

Despite joining the boycott, the Alliance of Patriots distanced themselves from European Georgia and the UNM, calling them the ‘formerly ruling regime’.

A number of independent MPs who left Georgian Dream over the aborted electoral reforms and controversial judicial appointments, including Eka Beselia, opted to continue to participate in parliamentary work.

The boycott is part of efforts by a wide spectrum of opposition forces in Georgia who have continued to demand a fully-proportional, party-list based system of parliamentary elections. They argue this would safeguard Georgia from power concentrated under one man or one party.

Georgian Dream vowed to scrap majoritarian single-seat mandates for the 2020 parliamentary elections in response to large anti-government protests last June only to backtrack on their promise in November.

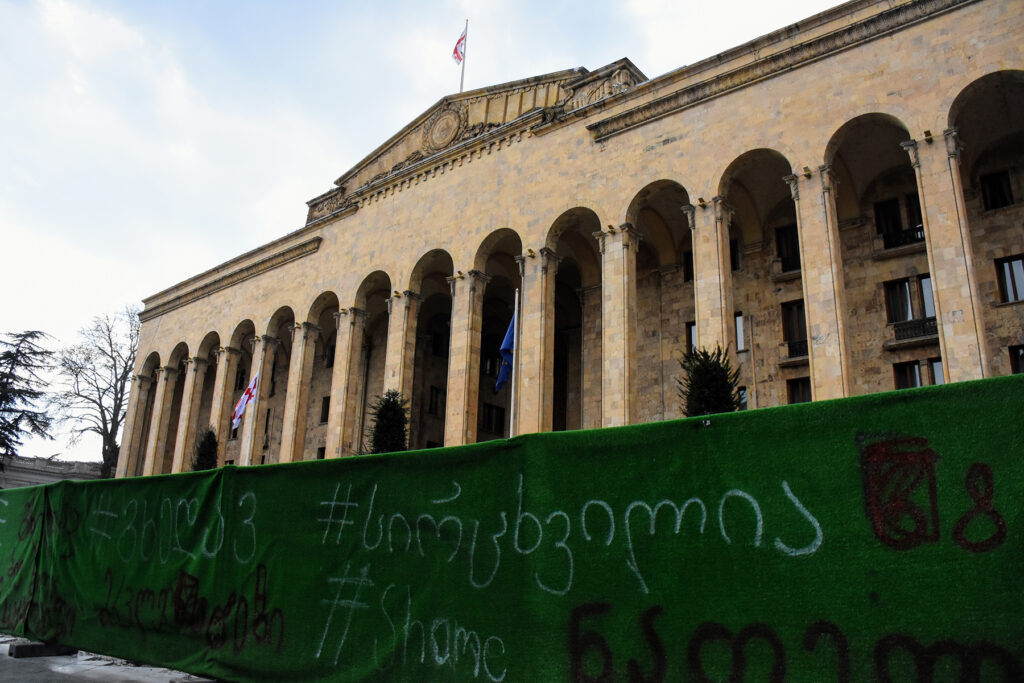

The change of heart triggered another wave of protests outside parliament in Tbilisi in mid-November.

Anti-government movement Shame and several opposition groups, including the UNM and European Georgia, renewed picketing parliament on 5 February but with fewer numbers than in November.

Activists and members of the opposition gathered outside the two entrances of the parliament and blew whistles as MPs arrived, demanding electoral reforms and ‘freedom for political prisoners’.

Since June 2019, the authorities have charged several leaders of the opposition, including UNM MP Nika Melia and ex-Defense Minister Irakli Okruashvili, over their role in a protest that turned violent in June.

‘Damage control’

The renewal of parliament coincided with a trip by Foreign Minister Davit Zalkaliani and Speaker Archil Talakvadze to Washington DC.

Critics have said the visits are damage control following a series of critical letters to the Georgian government from US lawmakers since December.

In their letters, US lawmakers reprimanded Georgia’s ruling party for politically targetted investigations, the Facebook fake accounts scandal, the hampered Anaklia Deep Sea Project, and for Georgian Dream’s failure to reform the election system.

The leaders of Georgian Dream have maintained that well-connected members of the formerly ruling UNM party, represented in local watchdog and rights groups, ‘misinformed’ Georgia’s foreign partners on the government’s records.

‘We have more communication with the government than with any other party’, noted Congressman Adam Kinzinger, one of the recent critics of the Georgian government after meeting Talakvadze on Friday.

The OSCE did not bring consensus

On 5 February, the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) published opinion on a proposed ‘modified German model’ of elections for Georgia.

Opposition MPs had requested they evaluate the proposal, but the results only exacerbated debate over whether it was an acceptable electoral model.

The ODIHR stated that amending ‘fundamental elements’ of the country’s electoral law should have been done earlier than a year before the election.

Speaking to OC Media, Georgian constitutionalist Vakhtang Khmaladze said that the ODIHR did not explicitly rule on the draft amendment’s compatibility with the Georgian constitution.

‘However, they did still indicate it did not require constitutional changes. If the opposite was true, I would expect them to say that it complied with international standards but the country’s constitution would need to be amended’, Khmaladze told OC Media.

‘The change would be implemented by amendments to organic law, which according to the Constitution, can be changed by a simple majority of votes in parliament’, the ODIHR’s opinion read.

Khmaladze said that anyone who wished to argue against the proposal on the grounds that it was unconstitutional should appeal to the Constitutional Court after it was passed.

On 6 February, opposition groups insisted the ODIHR had said there were no problems with the proposal’s constitutionality while Georgian Dream called them ‘incompetent’ for appealing to ODIHR in the first place.

The ruling party maintained that their ‘compromise’ to reduce the number of majoritarian mandates from 73 to 50 was their final offer.

A fifth round of talks between Georgian Dream and the opposition, brokered by diplomats in Georgia since 30 November, has not yet been announced.

7 February 2020

7 February 2020