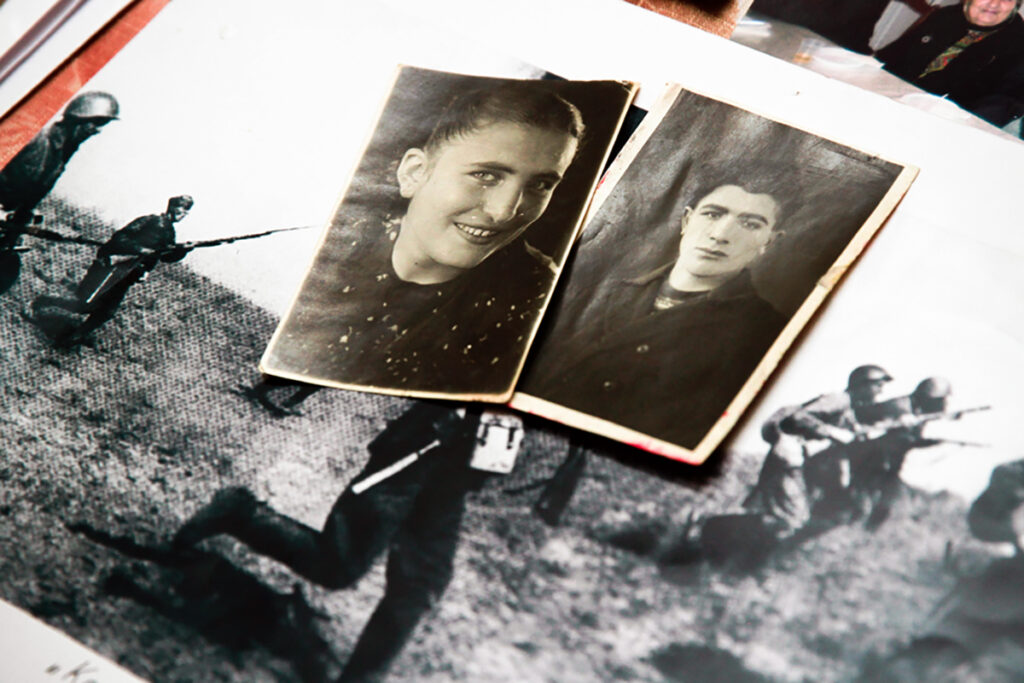

In 1941, aged just 17, Vardanush Zakaryan was called to serve in the Soviet Army — at the height of WWII. Shortly thereafter, her husband was also sent to the front. For the next four years, the two saw each other infrequently, but their love never died.

‘I went through a lot. I lost my dad when I was a child, so I moved from Tiflis, where I was born and lived, to Baku, where I began to live with my mom and stepfather. I was 12 when my mother died. So I grew up an orphan. One parent is buried in Baku, the other in Tbilisi’.

‘When I was 17, I moved to Armenia. I arrived on a new train, all dressed up — in a hat, with a reticule — all the guys gathered to look. Andre was among them. I married him and went to live with him in his village, and his family became my family. Two months after the wedding I was taken into the army: the war began’.

‘Andre and I both left for the front’

‘The head of the village called me, he had a military commissar over. They examined me, asked questions. I knew both Russian and Turkish, and they said that I must leave for the army. I replied that I would not go. They asked: “why is that?” “I’ve been married for only two months”, I said.’

‘My husband and I both cried, but what could I do? It was a state order for me to go, and it was neither in his power nor in mine to change anything.’

‘First, they sent me by train to Tbilisi; Andre was allowed to accompany me. Then I went to Batumi, where he was not allowed to come. I was sent to the aerostat unit. They inflated a large rubber aircraft there to take down [enemy] aircraft.’

‘I served in this division for several months until I was transferred to an anti-aircraft artillery unit. I was punished for standing up for another girl — I was the swiftest while the others were scolded for being slow.’

‘I stayed in the anti-aircraft artillery unit. With binoculars in hand, I conveyed where the planes were flying to and from. In our unit there were people of different nationalities, we did not differentiate between an Armenian or a Russian, a man or a woman, we became friends. There was a war going on, it was necessary to make friends, stay united in order to win.’

‘Soon after, Andre and I both left for the front. With the Taman Division, he reached first Gori, then Kerch [a city on the Crimean peninsula]. He was injured in 1943 when a mine exploded.’

‘One day, I remember coming back to sleep for two hours after being on lookout. As soon as I fell asleep, the girl who slept next to me came up to me and said: “Get up, the guy at the gate is waiting for you”. I saw Andre standing with a bandaged hand. The commander, at my request, released me from my duties for two hours. Andre and I talked, then I returned to the unit, and Andre went home.’

‘Not a month went by without us writing to each other. He worked, but came to Batumi quite often to see me — my commanders were already used to this. We would meet each other like that for around two years, until the war ended.’

‘On the night of 8-9 May, our unit was sleeping when we heard the alarm. We woke up and got into line. When we were told: “The war is over”, our joy knew no bounds, we were so overjoyed that nobody looked who they turned to kiss — the girls were kissing the boys, the boys were kissing the girls.’

‘We lived shoulder to shoulder for almost 80 years’

‘My children were born after 9 May — three daughters and two sons. Although I grew up an orphan, I raised my children well. Andre and I have 15 grandchildren, 45 great-grandchildren, and 6 great-great-grandchildren, and the numbers keep growing. I have lost count.’

‘All our lives Andre and I worked. We managed to go on holidays to all the cities of the Soviet Union. We also built a house, but it was destroyed in 1988 by the [Spitak] earthquake. Then we began to furnish the house again, but soon the war broke out in Nagorno-Karabakh.’

‘There were so many problems [after the collapse of the USSR], little attention was paid to veterans. In recent years, we have begun to be respected and appreciated again. Several years ago, Andre and I participated in the [Victory Day] parade in Moscow. We fought for the Soviet Union, but each of us fought for our little homeland, for Armenia, too, to live in safety.’

‘We lived well; and then this disease came [COVID-19]. The war began again [the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War]. I feel so sorry for all these dead and wounded guys. Andre was glued to the TV from morning to evening, watching all the news, getting angry. One day at home he just came down with heart disease. He passed away on the last day of 2020.’

‘I miss him: we lived shoulder to shoulder for almost 80 years, talked, did household chores together, slept together on the same mattress, under the same blanket for so many years. I would say, “let's do the laundry today”, he would reply: “let’s do that tomorrow” — we fought, of course, but lived well.’

‘He was a kind man, he supported everyone, he saved his monthly pension for his children, his grandchildren. This part he’d give to one, that one to the other — we never had money left.’

‘Now I am alone. I call my daughter, and instead of her name, I call her by my husband’s name. My daughter came from Kerch to look after me. I am a little weak, and I eat too little. When I get better, I want to go to Kerch: I miss my grandchildren. We lived well; if only just Andre were alive.’

‘I wish for everyone to live a happy life, [people] have already suffered so much, that's enough. War is very bad. It leaves an imprint on life, and you want to forget many things. May there be peace in the world.’

9 May 2021

9 May 2021